A beautiful yet unassuming 19th-century portrait of a mixed race woman believed to be Mary Ann Tritt Cassell went on view at the Baltimore Museum of Art late last month. It is making headlines for its unique place in the history not only of art, but of the nation.

The work is likely one of the first paintings commissioned by a person born into slavery in the U.S., and tells a fascinating story of a free Black family before emancipation. It’s also a rare work from the period to depict a person of color as a subject in their own right, and not in a position of servitude.

“As we think about building our museum’s collection and think about what stories are we able to tell, particularly in our historic galleries, this painting represents a wonderful opportunity,” Virginia Anderson, the Baltimore Museum’s curator of American painting and sculpture, told me.

Journalist James Johnston, who brought the painting to the museum’s attention, identified the sitter as Cassell, born in 1807 to Henrietta Steptoe.

Steptoe was born into slavery in 1779, at Stratford Hall in Virginia. The plantation would later be the birthplace of Confederate general Robert E. Lee, who was a second cousin once removed to both Steptoe’s owner, Ludwell Lee, and his wife and first cousin, Flora Lee.

When Ludwell Lee freed Steptoe in 1803, she moved to Georgetown, now part of Washington, D.C. That’s where Cassell was born, and went on to receive an education.

Georgetown was also home to James Alexander Simpson, a self-taught 19th-century portraitist and art teacher.

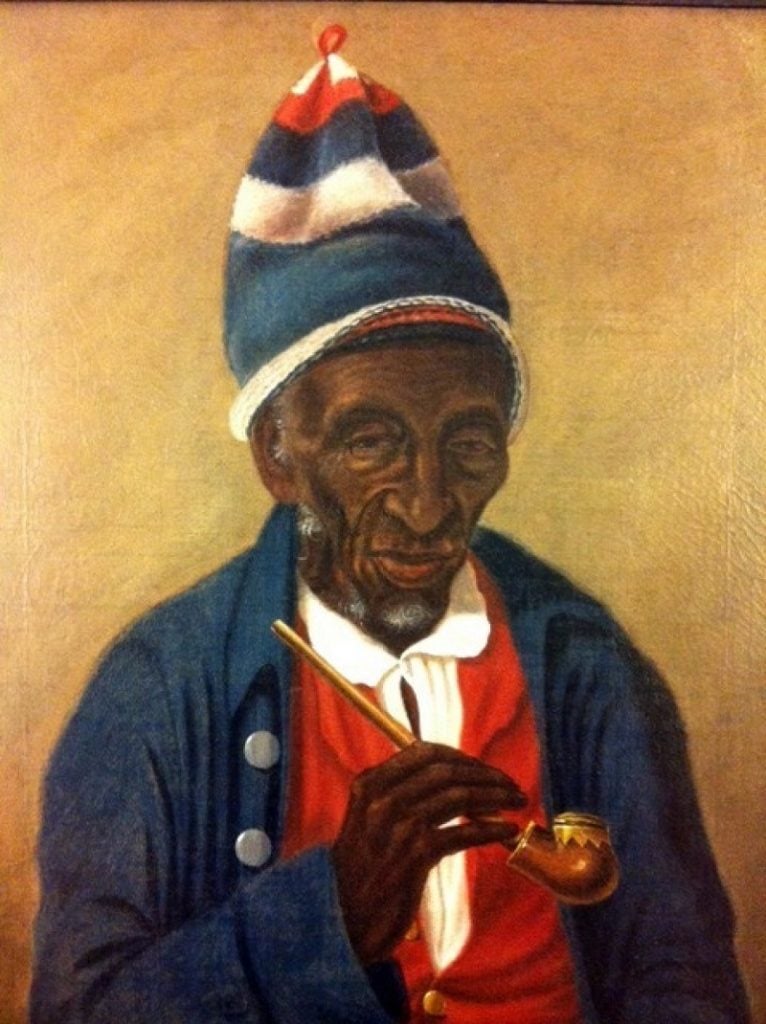

The neighborhood’s only professional artist, he had already painted a portrait of Yarrow Mamout, another member of the local community of free Blacks. (Part of the collection of the Georgetown branch of the D.C. library, it was on view in the “American Origins” exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in D.C. in 2016.) But Simpson kept Mamout’s portrait, suggesting it wasn’t a commissioned work.

James Alexander Simpson, Yarrow Mamout (1822). Collection of the Peabody Room, Georgetown Branch, District of Columbia Library.

Johnston believes that Steptoe, who worked as a midwife and nurse, bought and paid for her daughter’s painting herself.

A promised gift to the Maryland institution, the piece now belongs to Dorita Sewell of Florida. She and her late mother inherited it more than 10 years ago from a distant relative. They knew only that it was said to depict one of their ancestors, and that it might be the work of Simpson.

Then, last year, Sewell learned that Johnston was giving a lecture about Simpson. She decided to reach out to him to see if he could help her learn anything about the painting.

Now, the portrait, for years wrapped up and forgotten in Sewell’s apartment, is getting its moment in the sun. The painting went on view in Baltimore on June 26, and was the subject of an in-depth an article by Johnston in the Washington Post. (It was Hyperallergic that first identified Sewell as the donor.)

It will be the Baltimore Museum’s first painting by Simpson. Anderson was able to compare the work to other examples of his work owned by institutions in the region. She attributed the work to Simpson based on similarities in style and paint handling to the rest of the artist’s oeuvre.

“It’s a beautiful painting,” Anderson told me. “It’s really unusual. A lot of portraits by self-taught artists are super crisp, almost linear, and this has a very sort of soft focus quality to it.”

The work is also tied to the 19th-century colonization movement that sought to return free Black people to Africa. The movement had its critics, who saw it as a racist means of conveniently relocating the Black population. But Cassell’s husband, William Cassell, saw life on the African continent as an escape from the racism he encountered in the U.S.

By the time the two married in 1839, William had already spent time living in Africa with the Maryland Colonization Society, and was eager to return there. He moved to Cape Palmas, in present-day Liberia, in 1848, and Cassell joined him two years later.

She would live until her death in 1871, becoming a leading member of the community and running both the Episcopal hospital and orphanage.

Cassell appears to have left her portrait behind in the U.S. with her older sister, Rebecca. When Rebecca died in 1877, her will included “my sister’s picture,” according to researchers Carlton Fletcher and Jack Fallin. It was that painting that passed from family member to family member before making its way to Sewell.

“Anytime you see a painting like this that’s been handed down in the same family from generation to generation, that’s really exciting,” Anderson said. “And the fact that it is this portrait of a biracial woman really gives it wonderful historical significance, particularly in the way that it sheds light on that family’s history.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

References: this article is based on content originally published by Sarah Cascone on Artnet. You can read the full article here.