In 2023, a minor cultural scandal hit Carnac, northwest France. Mr. Bricolage, a home improvement chain, was opening up in the town, but to do so it had cleared away a field of ancient stones. Thirty-nine, to be precise, some dating back 7,000 years.

Archaeologists howled, the media arrived, and politicians bemoaned the massacre of cultural heritage. The residents, by contrast, largely shrugged. The mayor called the menhirs, the name for such standing stones, of “low archaeological value.”

This local reaction was to be expected. In the Breton language, Carnac means the place of the piles of stones and the surrounding countryside is duly marked with thousands of them. The megaliths are a part of the landscape and just as they have been ring-fenced for protection, they’ve also been stolen, removed for roads and car parks, and repurposed for local buildings, including a lighthouse.

The Carnac stones are often labelled the French Stonehenge. It’s a vague, unhelpful comparison. Stonehenge is concise and broadly contained; its Breton neighbor is a sprawling array of sites spread across miles of undulating maritime fields and on islands in the Gulf of Morbihan. It’s also some thousand years older.

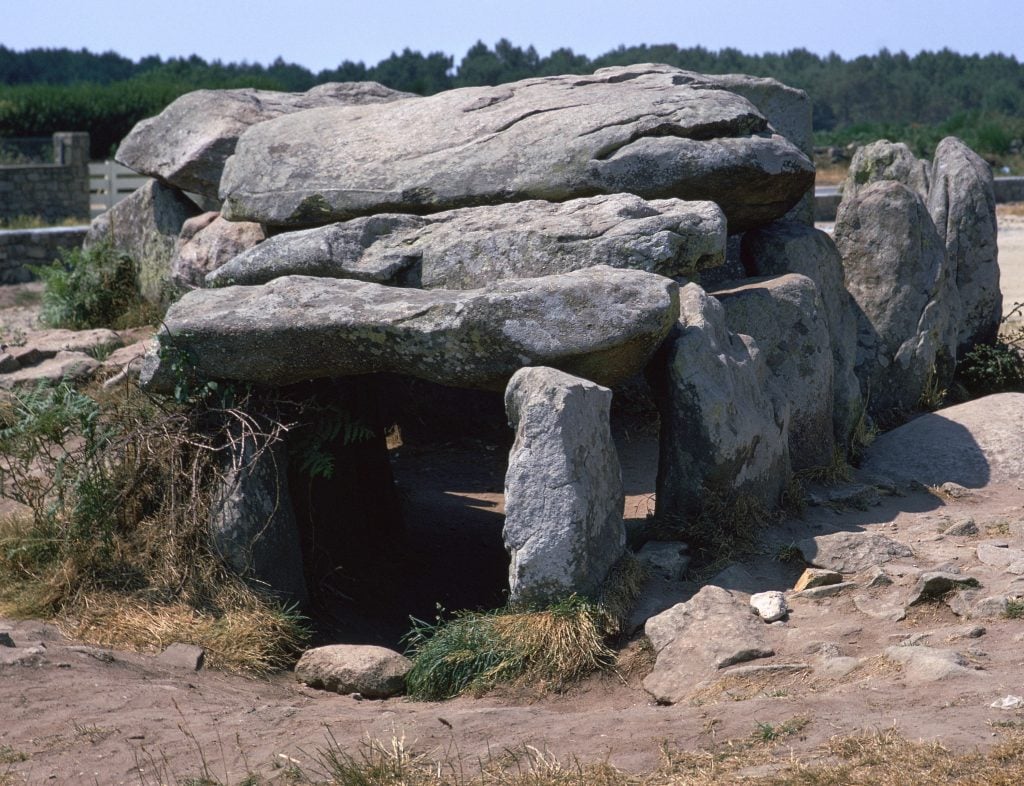

Dolmen at Kermario, Carnac. Photo: CM Dixon Getty Images.

Carnac is home to the world’s largest assemblage of prehistoric stone monuments, 100 or so key structures in all, made up of more than 10,000 stones. There are four major types of arrangements: alignments, linear rows of menhirs, some stretching half a mile in length; tumuluses, individual tombs formed around a mound; dolmens, collective tombs made of upright stones topped by overlaid stones that appear like dinner tables for giants; and enclosures, circles formed by megaliths.

The stones in question are granite and range from three to 20 feet in length. They were taken, and likely not quarried, from ridge lines in the surrounding area and moved into place using rollers and levers—artificial earth ramps were used to place stones on top of one another. The stone draggers in question were Neolithic farming communities that marked the landscape between 5,000 and 3,000 B.C.E.

The Saint Michel tumulus. Photo courtesy G. Marchand.

Little else is known of these pre-Celtic peoples, though the ornate engravings inside some of the dolmens, including those of cow horns, female figures, boats, and axes evidence a rich visual culture. Unfortunately, the corrosive acidity of the soil has destroyed much of the archaeological record, but items such as pottery, beads, copper axes, and flints have been recovered. Some originate from modern-day Spain and Italy, likely evidencing long-distance trade networks.

Societies are prone to explaining the unexplainable with fantastical stories that reflect contemporary concerns. At Carnac, the alignments were first mythologized as Roman soldiers petrified by Merlin. The arrival of Christianity in the region saw these Romans turned into pagan soldiers stalled by Pope Cornelius. During the Medieval doldrums, the ingenuity of Roman engineering was credited. Later, the stones became the sites Druids ritual. Today, New Age thinking posits aliens and UFOs.

Serious archaeological work began in the mid-19th century with the work of James Miln and his protege Zacharie Le Rouzic. They excavated several of the sites burial structures, including the tumulus of Saint-Michel, a 40-foot high tomb that looms over Carnac and is Europe’s largest mound grave. Archaeologists speculate that these structures also marked territory and stood of symbols of group identity.

Alignment stones of Menec. Photo: Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images.

The alignments, however, remain mysterious and strongly contested. There are three major alignments (Ménec, Kermario and Kerlescan) with each fanning out from enclosures placed on higher ground. Stretching east to west, they follow ridge lines separating the coastal plain from the interior with academics noting they follow the sunrise at solstices. The significance of these details is open to interpretation, but they seem suggestive of processional marking and spaces considered sacred.

On his visit to Brittany in 1850, the French novelist Gustave Flaubert was clear-eyed about the impossibility of “reconstructing a world” in Carnac, as if a science. Doing so dogmatically, he wrote, yielded results more barren than the stones themselves. However, his opinion that “the stones of Carnac are simply large stones” remains uncharitable.

Sometimes, archaeology gets big. In Huge! we delve deep into the world’s largest, towering, most epic monuments. Who built them? How did they get there? Why so big?

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

References: this article is based on content originally published by on Artnet. You can read the full article here.