When the artist Helen Frankenthaler, then in her early 20s, met Jackson Pollock, he was building an international reputation with his drip paintings, in which he flung enamel paints—the kinds used for household decorating, which were cheaper and more readily available than traditional artists’ paints—onto canvases which were laid on the ground. By allowing the paints to fall through the air, Pollock altered the conventional artist-artwork orientation, and removed his hand from the work.

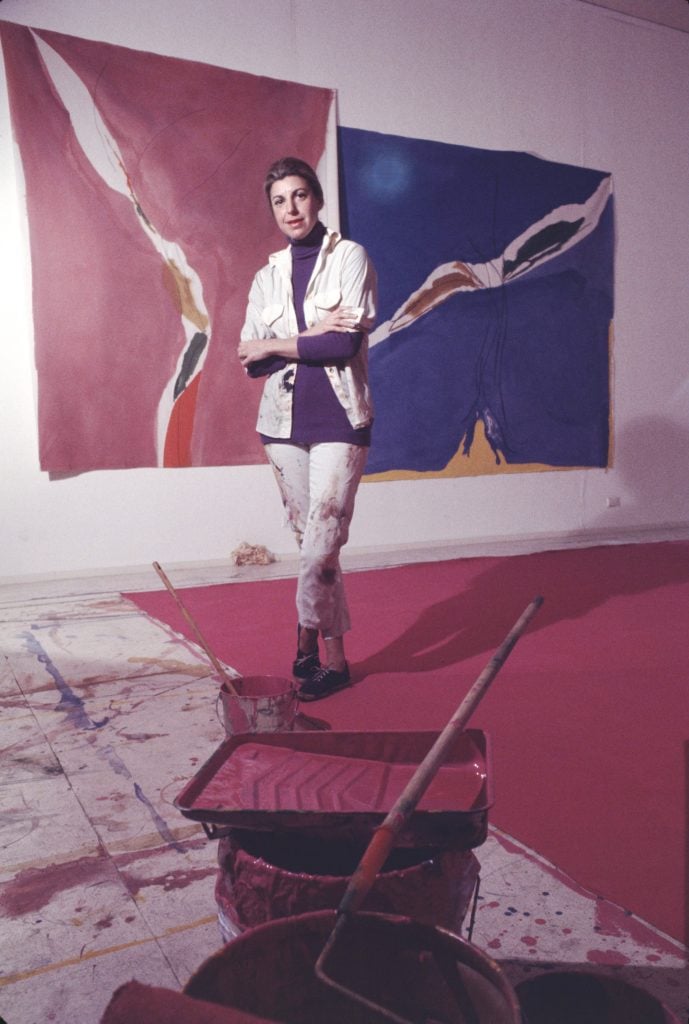

Helen Frankenthaler in her studio, 1969. Photo: Ernst Haas / Getty Images.

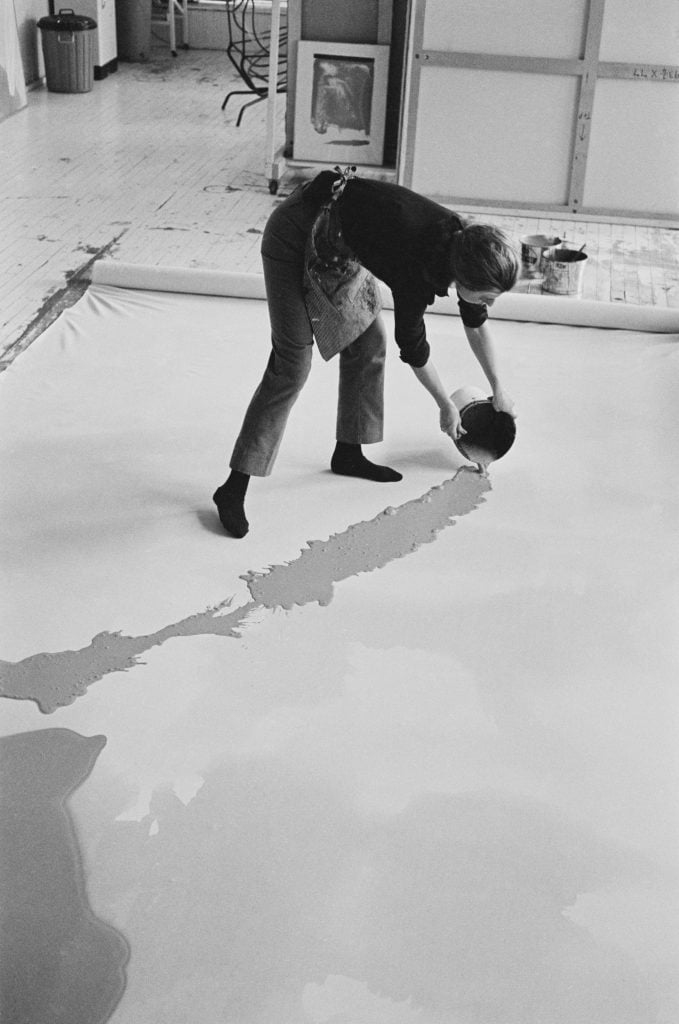

In 1952, with her painting Mountains and Sea, Frankenthaler developed her own unique technique for applying paint to her canvas. For the first time, Frankenthaler thinned down her oil paints with turpentine and poured them onto the canvas, allowing them to soak into the untreated fabric. In hindsight she said she made this decision due to a “combination of impatience, laziness, and innovation.”

Her thinned paints blended and merged across the canvas, and because they were soaked right into the fabric itself, the paint was not three-dimensional, like Pollock’s thick splatters of enamel. She would sometimes tilt the canvas and use brushes and rollers to manipulate the shape of the pooling color. In Fierce Poise: Helen Frankenthaler and 1950s New York (2021), author Alexander Nemerov describes how as a child Frankenthaler loved to pour her mother’s red nail polish in the sink and watch the forming patterns, which feels like a precursor to the soak-stain technique for which she would become known.

Helen Frankenthaler in her New York City studio, 1971. Photo: Jack Mitchell/Getty Images.

Her technique was praised by her then-boyfriend, the critic Clement Greenberg, who was an outspoken supporter of Pollock. But not everyone was impressed: some critics compared her paintings to menstrual blood (Joan Mitchell called her the “Kotex painter”). The New York Times referred to her work as “sweet and unambitious,” while others saw her work as simply derivative. In 1957 the painter Barnett Newman wrote the artist a letter after she appeared in an Esquire article about the New York art scene, saying, “It is time that you learned that cunning is not yet art.”

Helen Frankenthaler at work on a large canvas, 1969. Photo: Ernst Haas / Getty Images.

Regardless of criticism, Frankenthaler’s soak-stain works were hugely influential. The painter Morris Louis referred to her as “a bridge between Pollock and what was possible,” and along with Kenneth Noland she developed Color Field Painting, which celebrated flat and pure color, avoiding any illusion of three dimensions.

Frankenthaler innovated on her technique throughout the rest of her career, using watered-down acrylic paints which allowed her to expand her palette and increased the longevity of the works, as the thinner she used when she worked with oil paint was known to damage the canvases. The artist also managed to replicate the effects of soak-stain using woodcuts.

Want to emulate Frankenthaler and make your own stained work? The Oklahoma City Museum of Art has written a recipe for those looking to recreate her soak-stain technique at home.

What inspired Mary Cassatt‘s portraits of mothers? Why did Jackson Pollock paint on the floor? Eureka investigates the origins of artists‘ most famous works and techniques, unpacking how great art ideas happen.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

References: this article is based on content originally published by on Artnet. You can read the full article here.