Today, Moby Dick’s place in the literary canon is as weighty as its titular antagonist, but upon its release in 1851, the book barely made a ripple. “This is an odd book, professing to be a novel, wantonly eccentric and outrageously bombastic,” wrote the London Literary Gazette, before declaring it so torturous that readers might wish Herman Melville would take himself (and his whales) to the bottom of the sea.

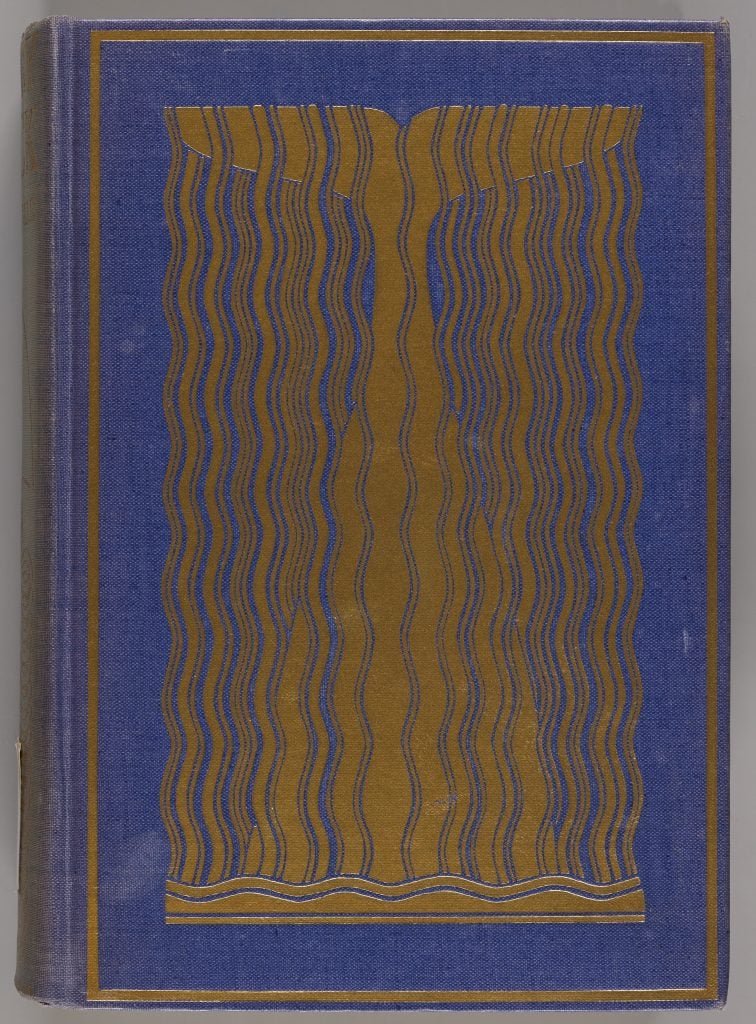

This reputation endured until the 100th anniversary of Melville’s birthday when American critics and authors revived his magnum opus. Illustration played a role. Case in point: Lakeside Press’s 1930 version, which sought to rival European publishing flair and quality. It turned to Rockwell Kent whose 280 faux-woodcut drawings capture the intimacies of whalers and render the novel’s central struggle as bold and biblical.

In a letter to Kent, Lakeside’s director of design, William Kittredge, promised to jump in a lake “if this book is not the greatest illustrated book ever done in America.” Such confidence was well-placed. Dan Lipcan considers it the definitive illustration for “the most persistently pictured of all American novels.” Lipcan would know having curated an exhibition at Peabody Essex Museum that delves through the maritime-rich collection of the Phillips Library to show the myriad ways artists and publishers have responded to Melville’s beastly book.

Rockwell Kent, illustrator, and Herman Melville, Moby Dick: or, the Whale (1937). Photo: courtesy Peabody Essex Museum.

“Moby Dick is this rich tapestry of ideas and concepts about humanity’s place in the world,” Lipcan said. “Each generation pulls different aspects of the novel out to apply to whatever the contemporary ideas of the moment are, I hope people realize through this exhibition how inspiration the novel has been.”

“Draw Me Ishmael: The Book Arts of Moby Dick” is an intimate two-room affair that in addition to offering graphic novels, pop-up books, paintings, and decadent cover art, uses maps and logbook drawings to contextualize the era from which Moby Dick emerged.

In 1851, whaling was at its gruesome, bloody peak. It was America’s fifth largest industry with the country operating more ships than the rest of the world combined. Melville experienced the thrills and the drudgery of whaling during 18 months aboard Nantucket’s Acushnet. He deserted while at anchor in French Polynesia and “Draw Me Ishmael” presents the ship’s logbook turned to the day in question. A tiny drawing shows a man running away. “Could that be Melville?” the museum label muses.

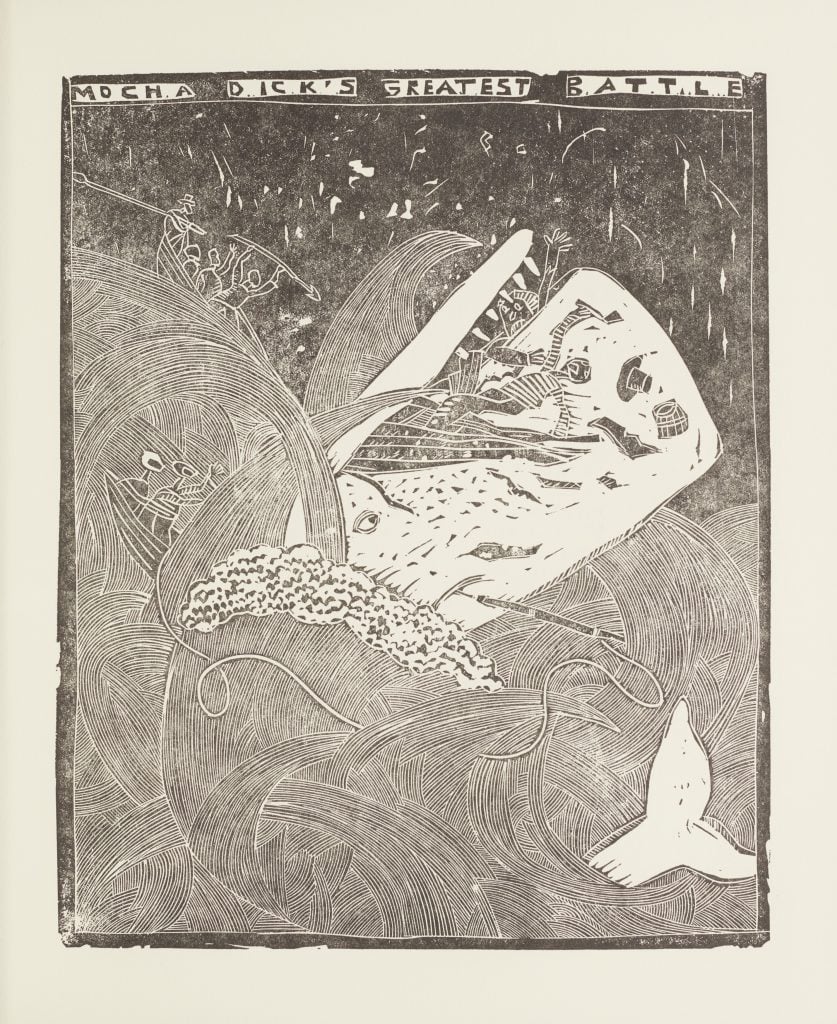

Randall Enos, Dan Smith and Virginia Cahill, The Life & Death of Mocha Dick (2009). Photo: courtesy Peabody Essex Museum.

This relationship between the Acushnet and Melville’s fictional Pequod stands in the exhibition’s entryway with maps showing their respective journeys across the oceans. Further inspiration was the legend of Mocha Dick, an albino sperm whale first spotted off the coast of Chile that eluded whalers for 30 years. A 2009 linocut by Randall Enos tells the story, offering Moby Dick’s muse as an omniscient saintly thing.

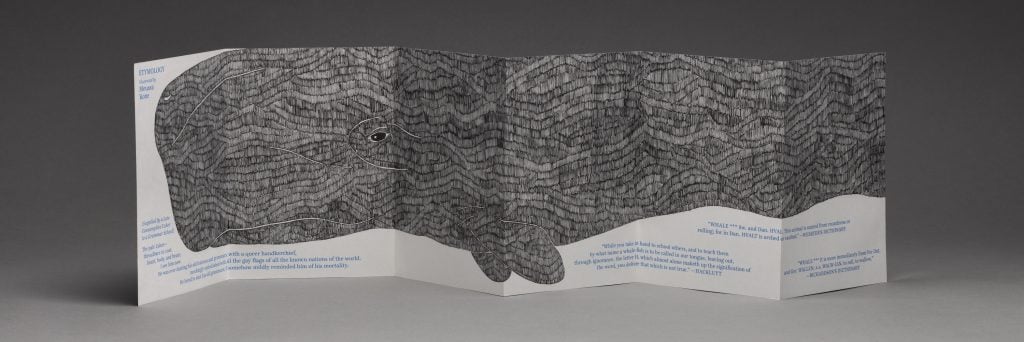

Moussa Kone, illustrator and Harpune Verlag, publisher. 2012. Photo: courtesy Peabody Essex Museum.

The novel may have taken three quarters of a century to attention, but once popular, it produced an unrivaled proliferation of illustrations. It’s easy to see why. The ocean, hardy whalers, and a leviathan are fertile subject matter. There’s the simple line drawings of Alex Katz from his time as Cooper Union student, the first color edition from Mead Schaeffer, and a garish splash of busy color from LeRoy Neiman’s 1975 effort. For breadth, the exhibition displays less vaunted releases from Penguin Classics, Barnes & Noble, and Wordsworth Editions.

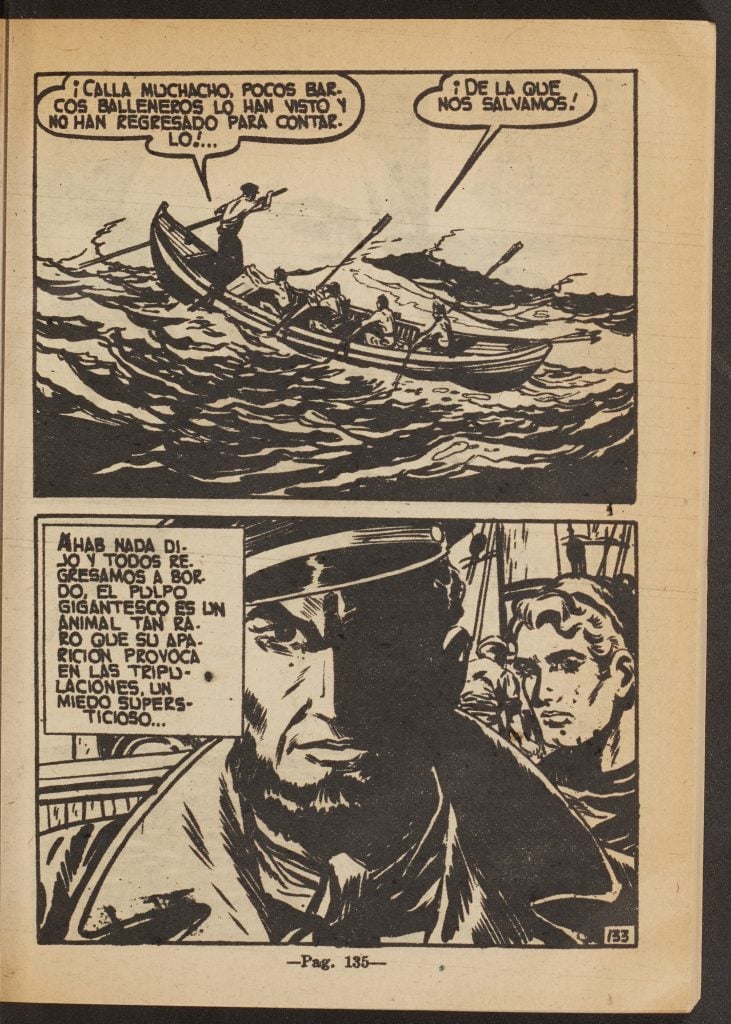

Luis Martínez, Othón Luna, and Victaleano León, illustrators; Eduardo Baez A. and Enrique Cárdenas Jr., text; Editorial Colecciones (Azcapotzalco, Mexico), publisher, Moby Dick (1957). Photo courtesy Peabody Essex Museum.

Even as the show lingers on a Mexican graphic novel, a Huckleberry Fin and Moby Dick crossover, elongated accordion books, and cyclopedic illustrations of all the whales classified in the novel, it’s far from an exhaustive accounting.

Doing so would be impossible. And, as Pequod’s loyal first mate put it, “only a fool would try it.”

“Draw Me Ishmael: The Book Arts of Moby Dick” is on view at the Peabody Essex Museum, 161 Essex St, Salem, Massachusetts, through Jan 4, 2026.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

References: this article is based on content originally published by Richard Whiddington on Artnet. You can read the full article here.