As explained in the exhibition Directed by Rembrandt, currently on view at the Rembrandthuis Museum in Amsterdam, the 17th-century Dutch painter could spend up to two days binding a turban worn by one of his subjects, because he wanted to depict the traditional headdress as convincingly as possible.

The same can not be said of Henri Rousseau, the French post-Impressionist who had a reputation for painting jungle scenes, despite never having seen one with his own two eyes. Having never once left his home country, the artist’s dreamlike paintings were instead cobbled together from works of literature, travelers’ accounts, colonial expos, newspaper articles, collectable catalogs, and the occasional visit to the Paris zoo.

Rousseau was born to a poor working-class class family in 1844. He grew up in Laval, a town in western France that, though it was certainly picturesque, wouldn’t readily be labeled as “exotic.” His first exposure to far-off places came when he landed a job at the French customs office in 1868. An entirely self-taught artist whose ultimately idiosyncratic style combines elements of primitivism and post-impressionism, Rousseau was never recognized by France’s artistic establishment. He did, however, earn the respect of rising stars like Pablo Picasso.

Henri Rousseau, Myself: Portrait (1890). Photo: VCG Wilson/Corbis via Getty Images.

His most well-known painting is called The Dream or Le Rêve in French. Created in 1910, the enormous image shows a naked woman reclining on a sofa in the middle of the jungle. Lions, birds, elephants, and other animals poke their heads through the dense foliage, which the artist painted in flat, unblended areas of color. Both the title and the image itself were inspired by Rousseau’s visits to the Paris’s Museum of Natural History and the Jardin des Plantes, a zoo and botanical garden.

“When I am in these hothouses and see the strange plants from exotic lands,” he said of the latter, “it seems to me that I am entering a dream.”

While many studies of Henri Rousseau focus on his painterly style—an article from the National Gallery of Art states that “the artist’s jungle paintings lack solidity, as if they were representations of theatrical décor, the gigantic leaves and petals minimally contoured so as to create the effect of overlapping cutouts”—his connection to the cultural histories of imperialism and orientalism is equally important to understanding his popularity.

Indeed, the social and political currents that gave birth to Rousseau’s jungle scenes are the same hat led to Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book, Joseph Conrad’s The Heart of Darkness, the more realistic academic paintings of Jean-Léon Gérôme, and other art that reflects or comments on Europe’s fascination with the so-called Orient, and the way in which Europeans imagine and fantasize about the countries they have colonized.

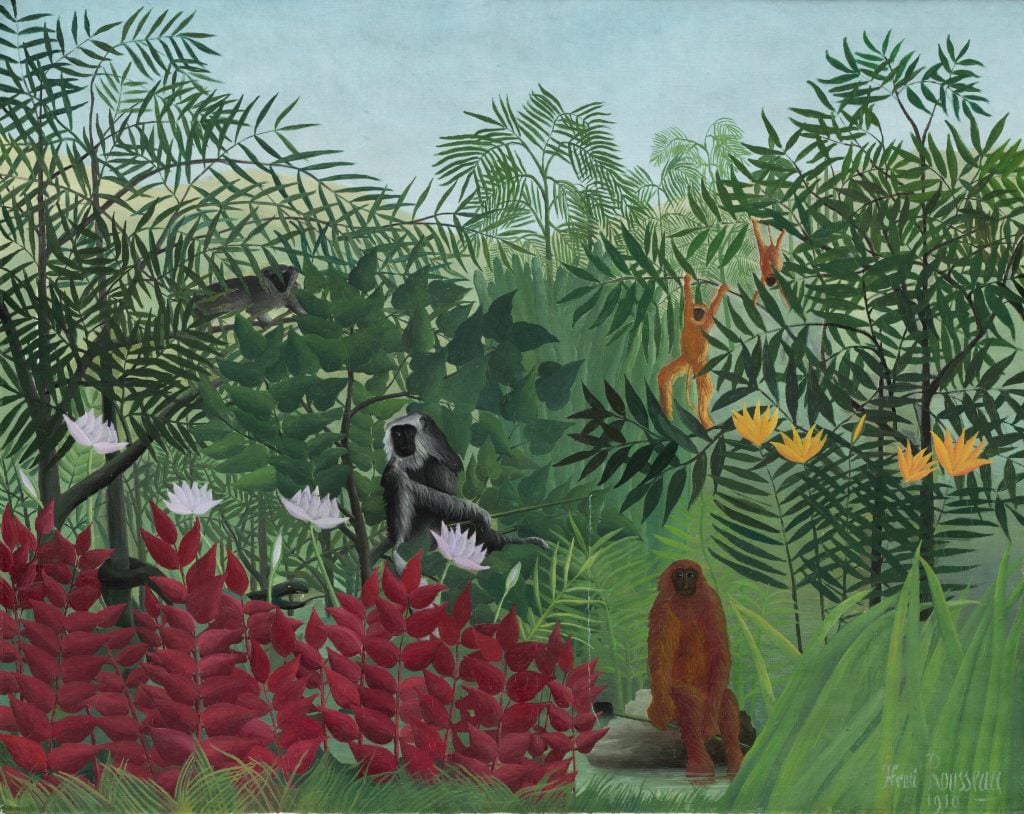

Henri Rousseau, Tropical Forest with Monkeys (1910). Photo: Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty Images.

While some of these fantasies are rooted in imperialist ambition, others are based on the largely innocent desire to escape the oppressiveness of urban existence and lose oneself in an unfamiliar, exotic and therefore quasi-magical world.

This sentiment is evident in another one of Rousseau’s jungle scenes, Tropical Forest with Monkeys, also from 1910. The Gallery of Art article interprets the “anthropomorphized primates […] not as true wild beasts, but rather as representing an escape from the ‘jungle’ of Paris and the everyday grind of civilized life.”

What inspired Mary Cassatt‘s portraits of mothers? Why did Jackson Pollock paint on the floor? Eureka investigates the origins of artists‘ most famous works and techniques, unpacking how great art ideas happen.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

References: this article is based on content originally published by on Artnet. You can read the full article here.