Art History majors face the worst employment prospects of any profession after graduating from college, a study by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York has found. The data, released by the Fed in February, became a talking point online this week, just as students close out the academic year and many start the job hunt.

Diving into the report, specifically it found that Art History majors face an unemployment rate of 8 percent, the most of any university major. The vast majority that have jobs are holding down positions they are overqualified, according to the underemployment rate of 62.3 percent.

While some educators I spoke to expressed skepticism at the findings, others believe schools could do better at preparing students for the work force.

“I am quite leery of those results as they may not take into account jobs art historians get in the gallery and museum world,” said Mona Hadler, an art historian and the head of the Brooklyn College art department. “I am not sure how they are compiling statistics. The arts provide many different opportunities for employment.”

But many were not so surprised by the findings, like Remi Poindexter, an art history professor and PhD candidate at CUNY’s The Graduate Center, who pointed to comments former President Barack Obama made as far back as 2014 when Poindexter was about to graduate with his undergraduate degree. Obama angered art historians and was forced to apologize after he said “folks can make a lot more potentially with skilled manufacturing or the trades than they might with an art history degree.”

“When I was in undergrad, people were talking about how dire the field was, so in a way it’s nothing new,” Poindexter said. “My advice as a teacher to anyone who wants to pursue art history is to have some kind of ‘professional’ double-major or minor as a fallback, just in case.”

Maura McCreight, another PhD candidate at CUNY’s the Graduate Center expected to complete her degree next year, has been teaching art history as an adjunct professor at Brooklyn College for five years but is preparing multiple resumes to again hit the job hunt. She has three resumes to cast a wide net in her search: an academic curriculum vitae for research professorships, a resume for teaching positions and a resume for research jobs at museums and nonprofits.

“There’s a hiring freeze within CUNY and I’ve been wanting to work at Brooklyn College full time for years,” she said. She noted that department chairs like Hadler face hurdles in opening up positions to new art historians because of institutional red tape. “It’s not like, ‘Hey, I think we want to open this position’ and then you immediately find funding. It takes years to do that in academia and it’s kind of mysterious how it really happens.”

Keeley Flynn, who graduated from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in May 2024, said she did not plan to attend graduate school or immediately pursue an academic route to art history, but did get accepted to one art history program and decided not to attend.

“I wanted to get work experience in a gallery or museum instead,” she said. Looking outside of academia, career paths within the arts sector are less defined and for that reason maybe somewhat easier to pursue.

She began trying for internships at large museums and other institutions in New York in January but ultimately didn’t get any offers. She instead found a job in installation and facilities at a museum in Madison. But she doesn’t consider herself underemployed.

“I studied both art and history and my current job at a contemporary art museum uses skills I’ve gained from both degrees,” she said. “The majority of folks I work with also have art degrees. Not sure if it’s required for my position, but it is the norm. But I’m not shocked to learn that more than 60 percent of grads are underemployed. It’s so competitive out there and there are not many entry level jobs available.”

Francesca Pessarelli, an associate director at the Ceysson & Bénétière gallery, graduated from the University of Wisconsin-Madison with dual bachelor’s degrees in Art History and French. Still, even if other jobs in the art sector may be easier to find, she feels lucky to have her job, even though she worked hard for it.

“To be totally honest, I didn’t really have a clue what the industry or job prospects looked like when I decided to study art history. I grew up and went to school in the Midwest where there wasn’t a huge emphasis on arts and culture as a career option,” she said.

Pessarelli originally started studying with the hopes of becoming a doctor but ultimately changed majors after having grown up loving art. But a passion for—and even a degree in—art are not always a guarantee to finding work within the field, and many jobs require a lot of experience for even entry-level positions.

Pessarelli interned at Ceysson & Bénétière as well as the Guggenheim in the curatorial department, straight out of college, she said.

“I won’t say it was easy because I worked my ass off as an intern making no money,” she said.

After, she applied for 20 different jobs and went through multiple interviews, she briefly took a job at another gallery in Chelsea working as a gallery assistant for a few months.

“It was crazy that this was supposed to be entry level and the competition was so steep,” she said. “There was no reason it should have been that hard to get a glorified personal assistant position paying barely over minimum wage.”

Unlike studio art majors and other arts-related degrees, which have marginally better job prospects according to the Fed data, Art History majors rarely learn any “hard skills” as part of their coursework that are transferable in any sort of way to other art-related careers. Some schools have been trying to offer more professional courses for arts majors to help them land jobs outside of academia, like Stony Brook University, which offers classes including a Gallery Management Workshop taught by Karen Levitov to Art and Art History majors. Levitov said the class gives undergraduate students “hands-on experience” working in a university art gallery.

“Students learn from professional staff as they participate in visitor engagement, gallery operations, installation, and events. In addition, the course provides instruction in museum and gallery administration, including curating, exhibition design, education, and marketing,” she said.

She continued: “The skills learned in this class can be applied to diverse career paths, including museum and gallery work, auction houses, foundations and art writing, as well as positions in a range of nonprofit organizations in marketing, outreach, fundraising, and administration. On the whole, courses in the arts provide students with skills in creative problem solving, analytical observation, research and writing, communication, and an understanding of global culture, and humanity, past and present.”

Yet such classes remain an outlier, Pessarelli said. Flynn agreed, adding that art history curriculums should require mandatory internships, stating it is unfair that institutions require graduates to have work experience without them being offered the ability to build that work experience up.

“Most art history programs don’t even have a single class on the art market,” Pessarelli contended. “There are all sorts of practical skills artists learn as a part of their formal education. Art History majors are systemically failed as professionals.”

She added that graduating students are faced with the worst art market in decades in the challenging post-2020 economic climate. “It’s really tough,” she said.

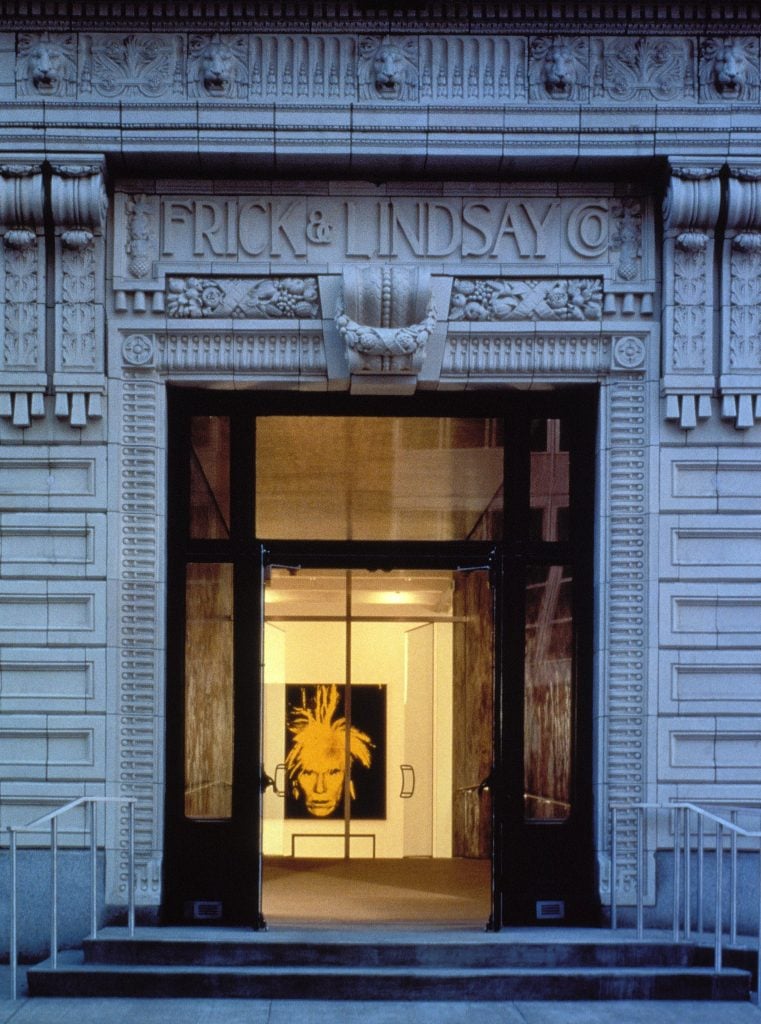

The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. Photo: Remi Benali / Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images.

Patrick Moore, former director of the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, suggested that all is not doom and gloom for Art History majors. “Someone with a specialized degree like Art History or an MFA may actually do better in an industry that views professional qualifications differently,” he said. “Many of us have ended up working in fields only tangentially related to our education.”

But he said that museums have traditionally been “quite rigid” in terms of job descriptions and qualifications, suggesting they could lighten up to provide graduates with better job prospects.

“During my time leading a museum, I started to see some loosening of those boundaries,” he said. “That doesn’t represent failure but a pragmatic approach to the complexity of selecting a career at a very young age.”

(Moore was recently named the director and culture lead of private investment firm Panarae Partnership Limited, a role that will see him advise South by Southwest London as its gears up to launch in Europe in 2025.)

Dan Law, a current associate director of the Warhol Museum, added that the needs of museums are changing and could adapt to place more graduates.

“The employment issue cuts both ways—institutions must be more innovative in how they deploy and hire for talent, and they have an obligation to communicate plans clearly and publicly for how talent can be part of their vision,” he said. But he added that job seekers need to adapt to the situation and expand their skillsets to be competitive, calling it “crucial for job candidates to be more than just one thing.”

McCreight echoed Law’s comments, stating that graduates with Art History degrees need to be creative with how they enter the job market. Now, museums and other institutions are looking for experience in the digital humanities—a field that she said could provide a lot of opportunities for job hunters.

“I sometimes think I should have gotten a Master of Library Sciences degree because some jobs want that in addition to experience in art history, like places still working in digitizing their archives,” she said. “These kinds of roles are really important and seem to be in demand, even more than museum curator positions, which are as difficult to get as professorships.”

Despite her critical remarks of the employment landscape, Pessarelli still said “there is an incredible value in pursuing Art History.”

“The classes I took challenged me harder conceptually than any philosophy, history, or literature class combined,” she said, adding that thinking abstractly and critically are important skills that many other degree programs don’t cultivate with the same rigor. “Rather than discouraging people from getting an Art History degree, I think it’s more valuable to encourage combining that degree with other subjects, learning some handy technical skills.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

References: this article is based on content originally published by Adam Schrader on Artnet. You can read the full article here.