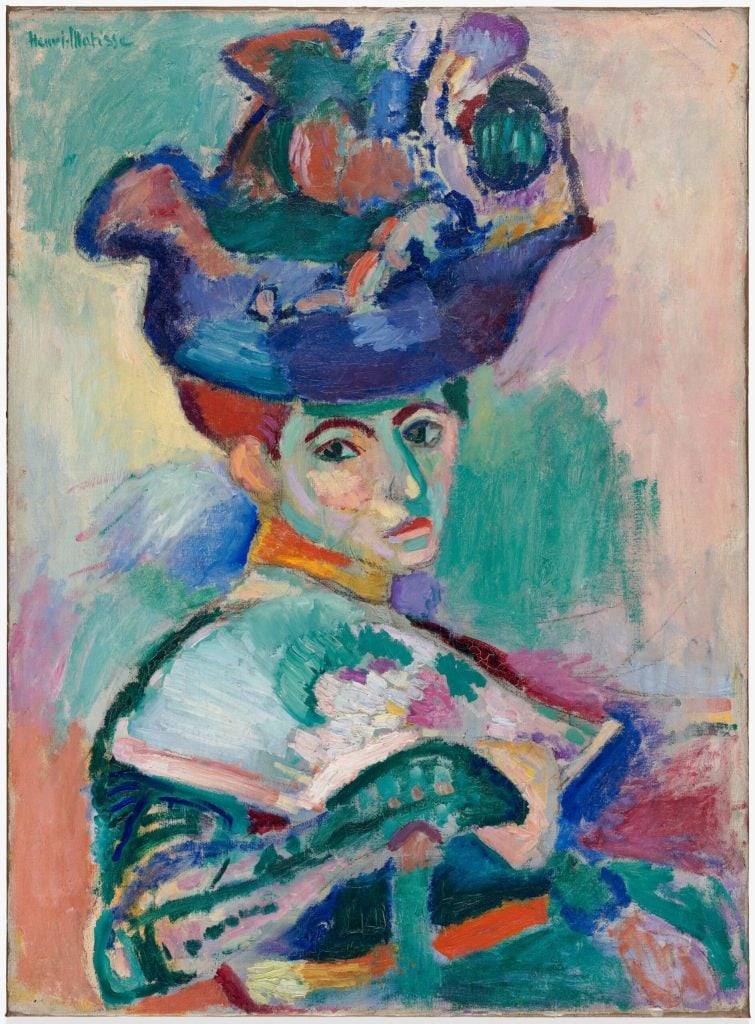

The Salon d’Automne in Paris may have been launched in 1903 as a liberal alternative to the staid Paris Salon, but even it was unprepared for what Henri Matisse unveiled in 1905. That year, the painter installed a portrait of his wife Amélie, her steady gaze anchoring a riot of colors. Amélie’s dress is depicted as a patchwork of pastel tints, her hat an explosion of vivid, undefined forms, and her face streaked with green. According to the Salon, the painting wasn’t just unlike Matisse’s earlier Neo-Impressionist works, it was downright unbecoming—a scandal.

Femme au chapeau so alarmed the Salon’s jury that Matisse was asked to withdraw it (he didn’t). It was only included in the show by the grace of artist Georges Desvallières, Matisse’s friend who was part of its hanging committee. Once unveiled, the painting caused more consternation. Among the many pans was critic Louis Vauxcelles’s, who, eying a Classical sculpture next to the work, deployed the phrase “Donatello chez les fauves” (“Donatello among the wild beasts”). It stuck.

Henri Matisse, Femme au chapeau (1905). Collection of the San Francisco Museum of Art.

Thus Fauvism was born—out of a tendency toward expressionism and instinct, and out of scandal, which would continue to dog its artists. But as Amélie, possibly echoing a sentiment shared by Fauvists to come, said of the reception to her portrait: “I am in my element when the house burns down.” Below, we trace the brief yet rich life of Fauvism and the “wild beasts” behind its wheel.

What was Fauvism?

Raoul Dufy, L’Apéritif (1908). Photo: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

While Fauvism had its sensational debut at the 1905 Salon d’Automne, its seeds had been sown long before, as modern artists sought to upend the grip of Impressionism. Van Gogh, Seurat, and Cézanne were inspirations. The paintings Fauvists produced are recognized for their highly expressive bent, which mined feeling from bold pigments, loose brushwork, and abstraction. Instinct guided the Fauvists, whose forms, though simplified, were vivified by a dynamic interplay of color planes.

Who was behind Fauvism?

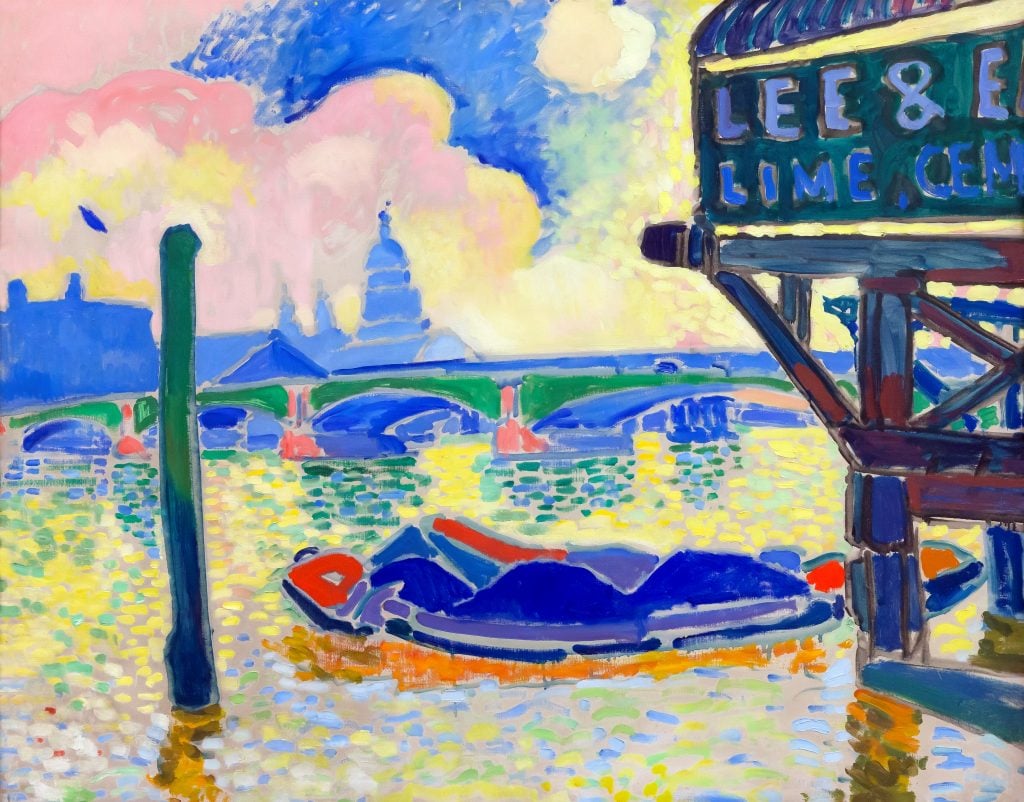

Andre Derain, Blackfriars Bridge London (1906). Photo: Peter Barritt/Avalon/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

We already know about Matisse. He painted the portrait of Amélie swiftly over the summer of 1905 while in the Mediterranean commune of Collioure, and in the company of his pal and fellow artist André Derain, who would become his partner in Fauvism. It was Derain who encouraged Matisse, as he painted Femme au chapeau, to treat color as he would any material like clay or wood.

Matisse and Derain had both trained with Gustave Moreau at the École des Beaux-Arts in the 1890s and fell under the spell of the Symbolist painter who once declared: “The evocation of thought through line, arabesque, and technique: this is my aim.” Matisse later recalled that Moreau “did not set us on the right roads, but off the roads.”

Maurice de Vlaminck, La Seine à Chatou (1906) at Christies. Photo: Michael Stephens – PA Images/PA Images via Getty Images.

At the time of Matisse’s experimentation, Derain was completing similarly striking landscapes, which expanded on the Pointillist technique with unnatural tones. Another future Fauvist, Maurice de Vlaminck, would be simultaneously inspired by Derain and Matisse’s Collioure paintings, as well as that of Van Gogh’s, to intensify the colors and atmosphere of his work.

Other artists including Henri-Charles Manguin, Georges Rouault, Henri Manguin, Raoul Dufy, and most significantly, Georges Braque, who also joined the Fauvist fray.

What are some other key Fauvist works?

Georges Braque, L’Olivier prés de l’Estaque (1906) on view at “Braque and landscape, from l’Estaque to Varengeville.” Photo: Anne-Christine Poujoula / AFP via Getty Images.

Like Femme au chapeau, Derain’s series of Collioure and London landscapes are Fauvist touchstones. De Vlaminck’s exuberant portrait of Derain and La Seine à Chatou (1906) are also of note, as are Manguin’s Jeanne au rocher (Cavalière) (1906) and Dufy’s Jeanne dans les fleurs (1907).

Braque, following his encounter with Fauvism at the 1905 Salon d’Automne, would produce works including Paysage près d’Anvers (1906), showing an emphasis on forms that would come to shape Cubism.

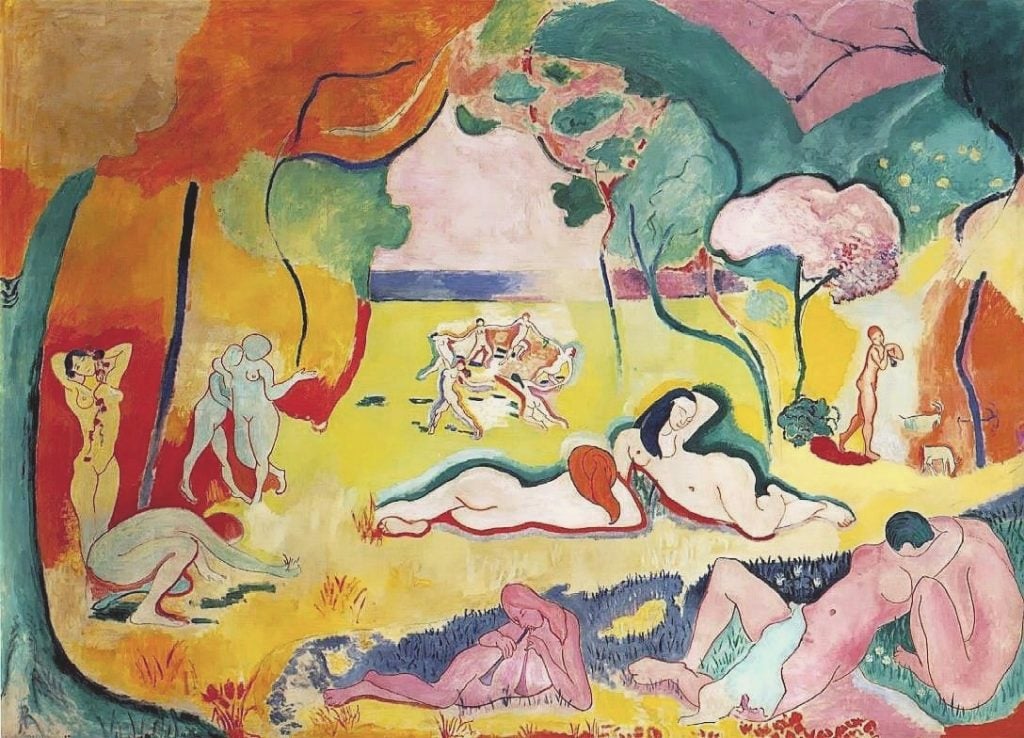

And of course, the OG Matisse would continue to create Fauve works, most prominently Le bonheur de vivre (1905–06), a bucolic, surreally colored scene that remains a Modernist masterpiece.

Did Fauvism continue to confound the public?

Henri Manguin, Morning (Lady at a bay shore) (1906). Photo: Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images.

It did. Fauvists exhibited at two more group shows, at the Salon des Indépendants and again at the Salon d’Automne in 1906, where critics continued to be dismayed at their use of colors and blend of techniques.

Perhaps the gulf that separated the Fauvists and everybody else is best illustrated by an anecdote from German painter Hans Purrmann, who once trained with Matisse. According to Purrmann, after the unveiling of Femme au chapeau, Matisse’s studio coworkers grilled him about the hat and dress Amélie was wearing that were “so incredibly loud in color.” An annoyed Matisse responded that the real items were “black, obviously.” He was joking.

Why are we still talking about Fauvism?

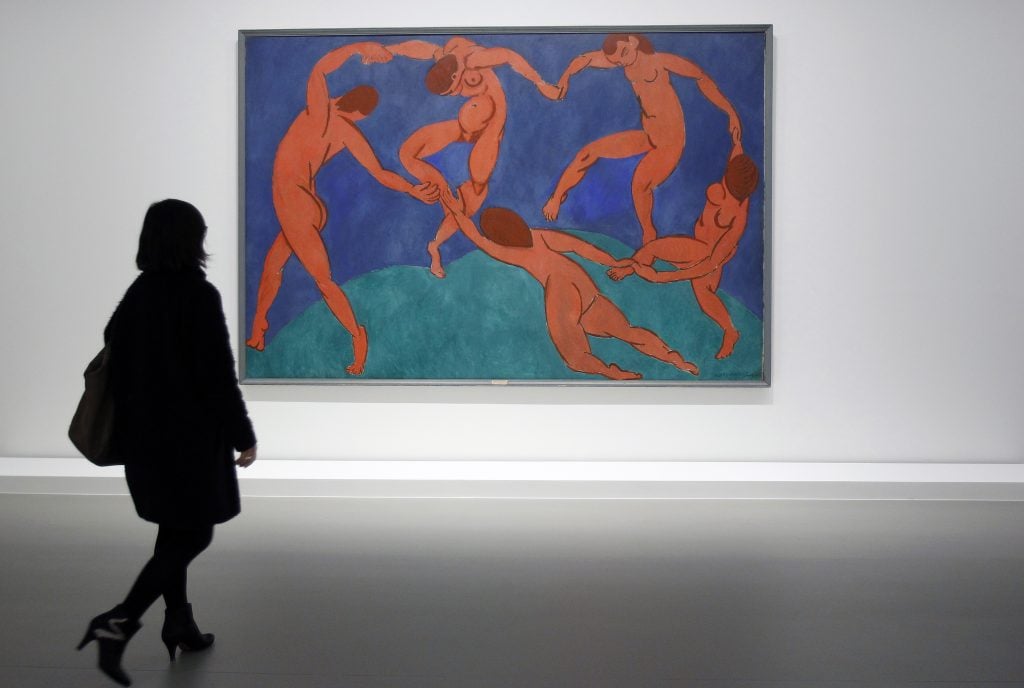

Henri Matisse, La Danse, on view at the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris, France, 2015. Photo: chesnot/Corbis via Getty Images.

As a movement, Fauvism had but a brief existence, spanning three to five years. By 1910, Matisse had moved away from the style, with La Danse, his energetic canvas of red dancers, marking his Fauvist swan song. Derain would go on to pursue neoclassicism, swayed by the renewed interest in Cézanne, who died during the 1906 Salon d’Automne. Braque would go on to found Cubism with Picasso.

However short-lived, Fauvism’s footprint can be found in Expressionism, Orphism, and other styles that forewent representation in favor of sensation. It was never a school, but it had its students. As novelist Gertrude Stein, who with her brother snapped up Femme au chapeau and Le Bonheur de vivre, wrote: “Matisse… created a new formula for color that would leave its mark on every painter of the period.”

For as long as there has been art, revolutionary movements have continually reshaped its creation and perception. Artcore unpacks the trends that have shaken up today‘s and yesterday‘s art world—from the elegance of 18th-century Neoclassicism to the bold provocations of the 1990s Young British Artists.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

References: this article is based on content originally published by on Artnet. You can read the full article here.