The imperiled Elizabeth Street Garden, located on city-owned land in New York’s Nolita neighborhood, is slated for destruction in September. Community members are desperately clinging to the last hopes of preserving the beloved sculpture park, which is set to become an affordable senior housing development.

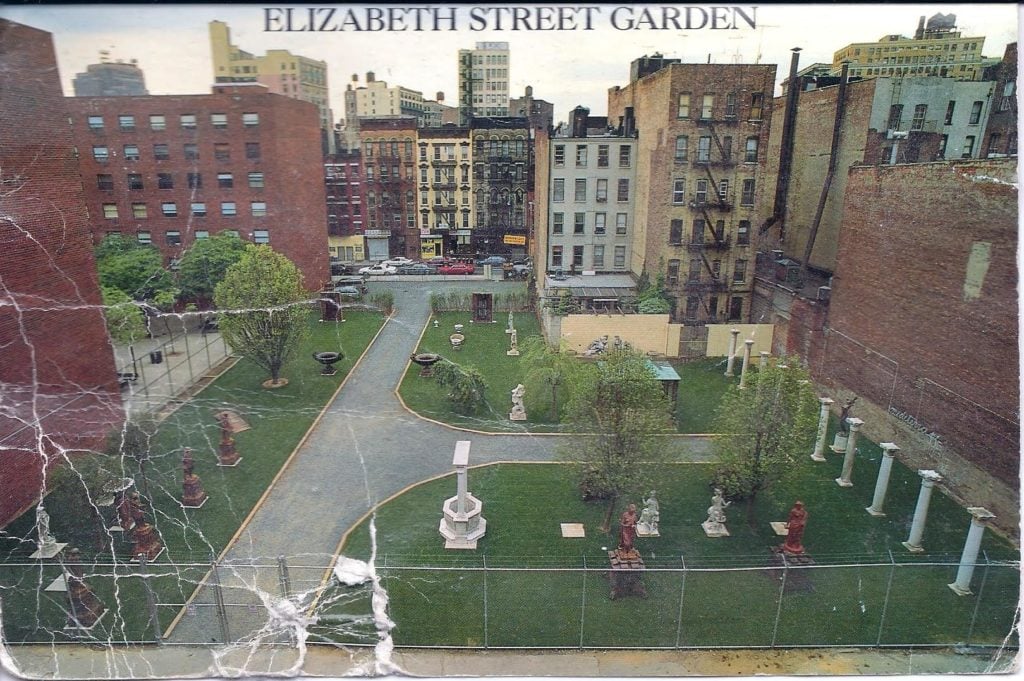

A peaceful oasis hidden in a bustling downtown neighborhood just east of Soho, the volunteer-run garden is filled with antique statuary, much of it salvaged from Gilded Age estates in the metropolitan area. It also hosts popular community events, including yoga classes, poetry readings, and outdoor movie screenings for some 200,000 visitors a year.

The garden has been fighting for over a decade to save all that. But those efforts received something of a one-two punch in the last two months.

On May 8, Judge Richard Tsai ruled against the garden in a 2021 eviction case, setting a September 10 eviction date. And on June 18, a six-to-one ruling from the New York State Court of Appeals gave the city the green light to proceed with the destruction of the garden to build affordable housing, despite concerns there had not been sufficient review of the project’s potential environmental impact.

Elizabeth Street Garden. Photo courtesy of ESG.

With the specter of demolition looming on the horizon, Joseph Reiver, the garden’s executive director, has vowed to continue the fight. “Our efforts to save Elizabeth Street Garden are not over at all,” he told me. “We’ve already appealed the eviction decision, and our legal team is working on our other options.”

(The lone dissenting opinion in the appeals court ruling, from Judge Jenny Rivera, found that the city “failed to take the requisite hard look at the climate change impact of the project, including the reduction in open space,” and therefore violated state and city environmental quality review laws.)

The garden has also launched a letter-writing campaign demanding Mayor Eric Adams save the space. It has already received to close to 350,000 letters. An alternate proposal from the garden suggests several other potential sites in the area where the city could build affordable housing, while preserving the garden as a conservation land trust.

A rendering of the proposed outdoor space at Haven Green, the affordable housing development slated to replace the Elizabeth Street Garden. Courtesy of Haven Green.

What’s at risk of being lost

Advocates for the garden maintain that it is a much-needed public green space in a neighborhood lacking in parkland, as well as a unique example of landscape architecture.

“The garden is a work of art in its own right,” Reiver said.

It was Reiver’s late father, Allan Reiver, who transformed what was once an abandoned lot into the verdant patch of land that it is today. The owner of a nearby antique shop, the Elizabeth Street Gallery, he began leasing the land from the city in 1991 for $4,000 a month, clearing it of trash and detritus, including two abandoned cars.

Allan planted trees, a lawn, and gardening beds, and filled the land with neoclassical stone sculptures and architectural remnants from his gallery, with marble columns and sphinxes.

Most notable is a 20th-century limestone balustrade from Lynnewood Hall, an estate outside of Philadelphia. Today, it lines the garden’s central pathway, punctuated with two large lion statues—in essence creating a sculpture by Reiver and his father. There’s also an iron gazebo designed by the Olmsted Brothers, sons of Frederick Law Olmsted, for the Burrwood Estate in Cold Spring Harbor in 1898.

The Elizabeth Street Garden’s limestone balustrade and one of its lion sculptures. Photo courtesy of the Elizabeth Street Garden.

The Cultural Landscape Foundation, which has been part of efforts to save the garden for nearly six years, believes the garden is “a nationally significant cultural landscape and work of outsider art,” Nord Wennerstrom, the organization’s director of communications, told me in an email. And despite the recent setback in the courts, “we’re committed to continuing.”

In 2013, after the city first announced the plans to build senior housing on the site, members of the community began working with Allan to open the garden through the main gate. The volunteers formed the Friends of Elizabeth Street Garden, creating regular visiting hours and programming. (The organization has not been involved in the site’s operation since 2017, when the garden formally organized as a nonprofit.)

A City Hall spokesperson told me that the garden only began welcoming visitors after the site was designated for an affordable housing project. But Reiver contends that is a misleading argument.

“Yes, the campaign to save the garden started when people found out they wanted to destroy it—because people wanted to show how much potential it had and how valuable and amazing it was for the community,” he said. “Before, it was really just my dad, and there wasn’t the means to keep it open. Now we have over 400 volunteers in the garden. It’s all done at no cost to the city, and it’s a fully functional nonprofit.”

Elizabeth Street Garden in the early years. Photo courtesy of ESG.

A long history

The garden’s history as a public green space dates back to 1904, when a newly built public school opened on the lot with a playground and recreation space that included a flower garden. The city tore down the school in the 1970s. In 1981, the city built the Little Italy Restoration Apartments, or LIRA, a 152-unit Section 8 affordable housing building, on the southern half of the lot.

The space that is now the Elizabeth Street Garden remained empty, with the Department of Housing, Preservation, and Development granting LIRA permission to use the area as recreational space for the public. Instead, it became a dumping ground—until Allan got permission from the community board to lease the lot, with the requirement he maintain it as a park-like environment.

At first, the garden was an outdoor showroom for the Elizabeth Street Garden, but in 2005, the business moved into the building next door. That’s when Allan put up a sign inviting the public to visit the garden through the shop. Slowly, the community began to appreciate the hidden garden just beneath their noses.

The garden’s trouble began quietly, in September 2012, when then-City Council member Margaret Chin got approval to add the Elizabeth Street Garden to the proposal for the Seward Park Urban Renewal Area, now known as Essex Crossing, to ensure the development of five lots on the Lower East Side had enough affordable housing units.

In the process, the city transferred ownership of the Elizabeth Street Garden lot from the Board of Education to the New York City Housing Authority. The rest of SPURA is located in Community Board 3, and the city did not inform Community Board 2, where the garden is, about this change.

“There was no outreach to say ‘is this OK? Do you want this?’” Jeannine Kiely, a member of Community Board 2, and the president and co-founder of Friends of Elizabeth Street Garden, recalled.

Community Board 2 would later vote to deny the development application for the garden, and advocates for the garden launched a legal campaign to secure its preservation. Nevertheless, the project was approved by New York’s City Planning Commission in 2019.

When Allan died in May 2021, the city terminated the garden’s month-to-month lease and began eviction proceedings.

Statues and the Olmsted Brothers gazebo in the Elizabeth Street Garden. Photo courtesy of the Elizabeth Street Garden.

What the community needs

If the garden is indeed destroyed, the city will turn the land over to a private developer to erect an mixed-use building called Haven Green. It will include retail space as well as 123 affordable studio apartments for seniors. There will be units designated for the LGBTQ community as well as the formerly homeless and existing residents of the neighborhood.

Haven Green will also maintain some green space that will be open to the public, as well as opening part of the courtyard of the adjacent LIRA, for a total of over 15,000 square feet of public open space.

“We’re very excited about the new open green space that’s coming to this site in addition to much needed affordable housing,” a City Hall spokesperson told me in an email. “This is a false choice between open space and housing—we can achieve both through the proposed plans for this site.”

It’s that same language, of a “false choice,” that the garden’s defenders have been using for years.

A rendering of Haven Green, the affordable housing development slated to replace the Elizabeth Street Garden. Courtesy of Haven Green.

But when the they suggested 388 Hudson Street, a city-owned vacant lot in the neighborhood, as an alternative site for the project, the move backfired. Instead of sparing the garden, the city decided to move forward with development on both lots. (A NYPD parking lot at 324 East 5th Street is also set to become affordable housing.)

The garden’s adherents also take issue with the city’s insistence that Haven Green will offer both public green space and affordable housing. The site plan includes a garden of just 6,700 square feet—compared to the garden’s current 20,000 square feet. The rest of the “open space” includes a 2,000 square foot covered tunnel that will be lined with retail shops, and the paved area commandeered from LIRA.

“The way they used the courtyard of LIRA is quite devious, because the residents in that building never agreed to that,” Reiver said. “And it’s misleading for the city to say we’re preserving this amount of open space. They would bulldoze everything. The whole place would be a construction zone that would be blocked off for two-plus years.”

For Reiver, the bottom line is simple. His father conjured a bit of only-in-New-York magic in of a neglected junkyard, and if it is lost, it will be lost forever, he said. “The city will never build something like the Elizabeth Street Garden.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

References: this article is based on content originally published by on Artnet. You can read the full article here.