“As a foreigner, it couldn’t feel more English,” said Canadian artist Megan Rooney of her central London studio. This space is at the very top of a Victorian building formerly known as The Royal Ear, Nose, and Throat Hospital and has “a shabby balcony” overlooking Britannia Street. Rooney has a second studio, too; this one occupies a “very new pristine building” in Vauxhall, just south of the river, which offers a comparatively contemporary view of the capital. “The area around it gives me the impression I’m walking through a sketch-up model!” she said. “At any moment you could touch a wall and walk right through it. Utterly bizarre.”

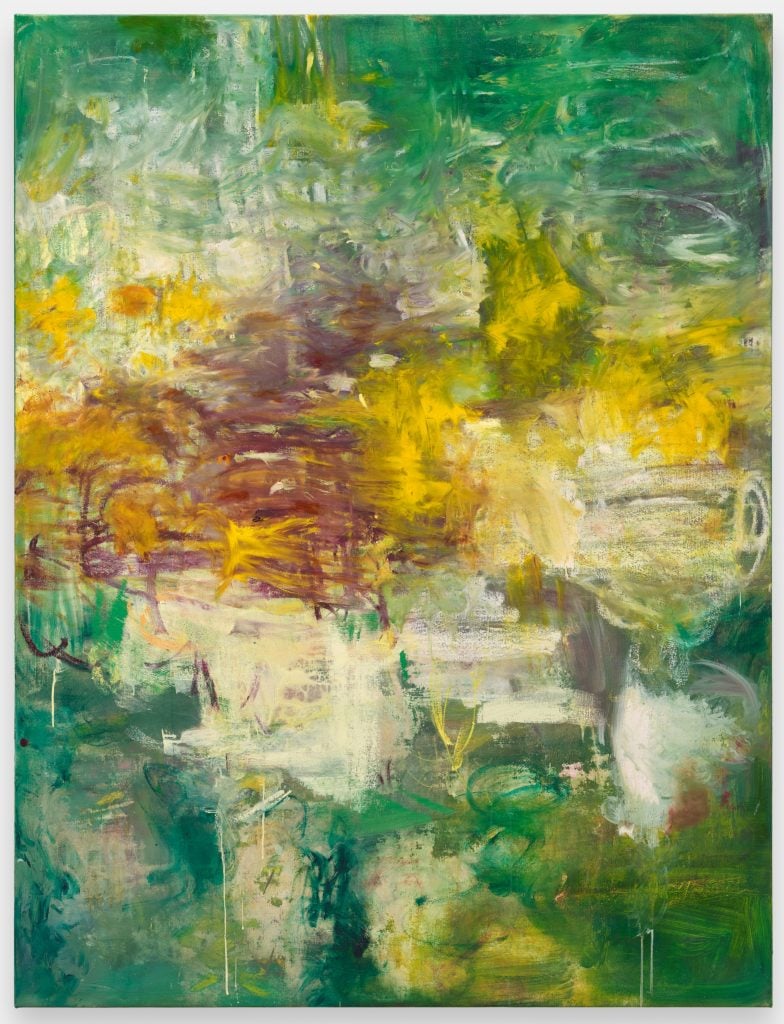

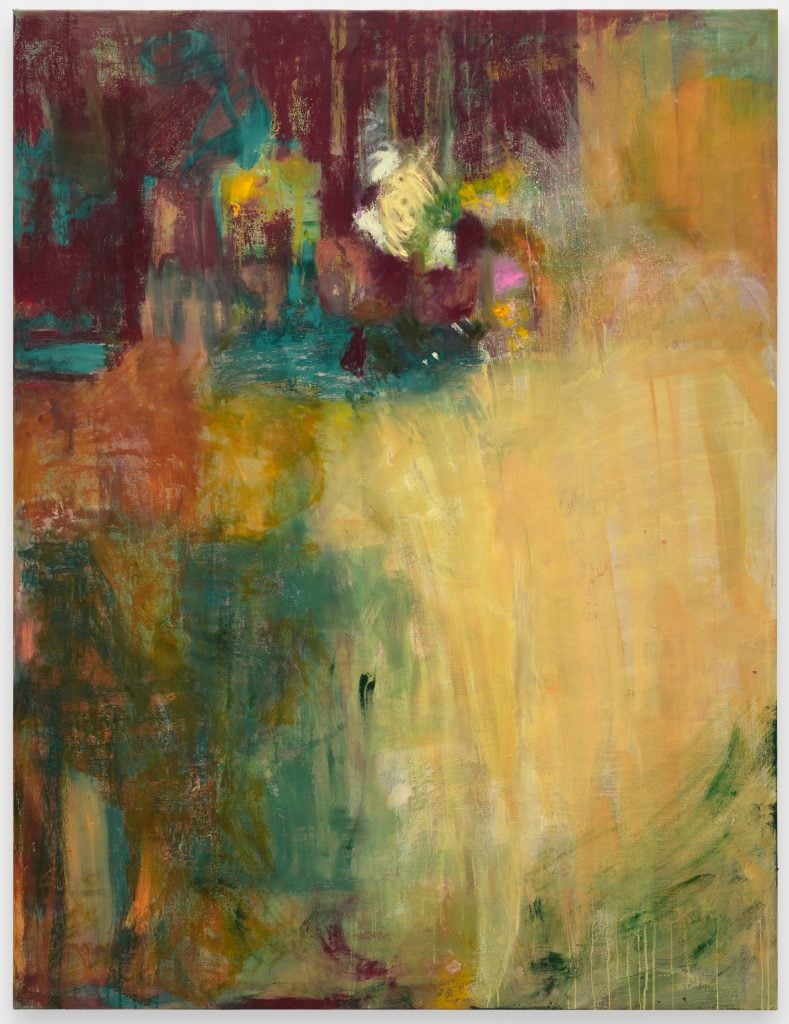

Rooney is best known for her large-scale, lyrical, painterly abstract canvases. These dreamlike compositions sometimes hint at narratives, with recurring characters and motifs, but their stories remain fundamentally enigmatic. “I think of my paintings in family groups because they need a kind of sibling rivalry in order to create a feeling of tension in the studio (something to ride against),” she said.

The artist has spent the past year working on “a new family of paintings” that have just gone on view at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge (until October 6). The exhibition builds on recent momentum for the artist and follows her 2023 Paris exhibition “Flyer and the Seed” with Thaddaeus Ropac.

“We’ve had a tremendous response from collectors from the moment we started to work with her, for her ‘wingspan’ size canvases, for large-scale commissions and her works on paper,” said Julia Peyton-Jones, senior global director at Thaddaeus Ropac. This June, the gallery presented Silent, Spring, Singing (2024) at Art Basel and her work was also on view this year at both Frieze, New York, and also West Bund, China.

Peyton-Jones called it “a consciously global spread so that international collectors have the opportunity to see” the work in-person. “It’s extraordinary to see how her work draws people in,” she added. The strategy seems to be working: in recent years, Rooney has been acquired into the Fondation Louis Vuitton collection, Paris, the Museum MACAN, West Jakarta, and the Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw, as well as the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami. The work on view at Basel last month sold for $76,300; generally, prices for Rooney’s works start at £20,000 ($25,300), for works on paper, while her monumental canvases begin at £75,000 ($95,000) and upwards.

For the artist, however, her process has remained largely unaffected by these major primary market developments. It might come as a bit of a surprise given her focus on painting, but Rooney initially trained as a printmaker, working in intaglio and etching.

“It means I like to work in reverse,” she explained, “I remove layers of paint to unearth the forms and colors that lay buried within layers of paint. It takes a lot of different types of energy to make what I think is a strong painting in the end.”

Megan Rooney, Sowing Sky (2024). Photo: Eva Herzog.

These forces need to be kept in the right balance, according to Rooney. “This is something I am only now starting to understand some ten years in,” she said. “It cannot be all hot, all emotion, all passion. It cannot be all peace and all rest. It needs aggression and destruction, but too much of this won’t do either. If you plan everything beforehand and rush the surface, you end up with something superficial.”

Given the work’s ambition, as well as its occasionally unruly nature, it is not uncommon for Rooney to spend a year on one family of paintings. “You have to establish a relationship with it and for this you need time,” she said. “My paintings are like portals holding the weight of time.”

What’s it like working across two studios and how do they differ?

[At the King’s Cross studio] the light is incredible, as it pours in from all sides and this has hugely impacted the way I work as my paintings have their own unique ecosystems and sort of act as weathervanes or barometers.

I always paint from a position of motion, so I like to run to Vauxhall where my other studio is. I collect images and weather temperatures (wind, run, sun, heat) so in a way I’m already painting before I arrive. As these images and impressions lodge in my memory bank and spill out when I’m faced with a blank surface.

Megan Rooney in the studio in 2024. Photo: Megan Rooney.

Just a short five-minute walk away [from the Vauxhall studio], you get a good bit of London where the original fruit and veg/flower market is. The place is buzzing with activity and color. I wander around and look at enormous containers brimming with bright orange carrots; the next one is full of pale green cabbages or electric lemons and so on. In a way, it’s like walking through a colossal painting. So I go there almost every day, drink a coffee with the food packers, and steal some images for my memory bank.

For your new show at Kettle’s Yard, you painted in situ. Was it strange to be pulled out of your usual studio space?

My studio is also mobile! I paint on trains, in cafes, and always in hotel rooms. A few months ago, I started making small works on paper that I refer to as sidewalk paintings made spontaneously when I see something that moves me or catches my attention (a bird in flight, a bit of exploded trash, a wonky tree pushing the concrete sidewalk out around, a wailing baby, a woman’s silk dress blowing in the wind, a reclining figure emerging between the trees). I’m always trying to get the outside [world] in paintings. Then of course my memory acts as a kind of umbilical cord between what I see and what slips out onto the canvas.

I’ve been making a colossal 360-degree wall painting inside Kettle’s Yard. It’s risky because I do not work with preparatory sketches; it’s not ‘paint by numbers.’ I spend a lot of time tracking in the space (by that I mean moving). I come from a dance background, so it’s important to feel how my body responds to the architecture. I think of my murals as a kind of three-way informal collaboration between my body, the forklift, and the architecture, which is always unique to the space (my last public mural was with Frank Gehry; this time it’s Jamie Fobert!) Radically different!

Scenes from Megan Rooney’s studio in 2024. Photos: Megan Rooney.

What inspired the murals?

My murals have a strong attachment to the ancient world and the history of mark-making on walls, one of the earliest forms of storytelling that connects across generations. The very simple impulse to leave a trace, to make a mark, to say I was here. While I was working on the mural, it was announced that archaeologists had uncovered a blue room in Pompeii. This greatly moved me and blue took hold of me.

I imagined the mural would be hot, reflecting a change from spring to summer. Light conditions impact how I respond to color. During the mural’s birth, we had a great deal of rain and wind, in keeping with what has been the wettest spring in the UK since records began. In the end, color rebelled, and blue chased out yellow.

When you feel stuck, what do you do?

When I’m feeling blocked with a painting, I usually move over to another one in the family. This is why that family clan dynamic is so vital. But you can’t always abandon the work and move over to something else. Sometimes you have to process that frustration (form fighting color, color rebelling against the form, and so on) directly on the painting!

I can be quite brutal and cruel to them, inflicting all sorts of terror and madness as the days unfold, but the painting must go through this process to develop its own personhood. It’s like life: the older you get, the more experiences you have.

Megan Rooney, Flashed On (Hours) (2024). Photo: Eva Herzog.

What do you look to for inspiration in the studio?

I also drink an obscene amount of coffee in my studio during the day and I eat peanuts with tomato juice at night. Always. I listen to a lot of Vivaldi and Max Richter when I need to fly. When I need to hover, I listen to the Iranian pianist and composer Javad Maroufi. At night it’s jazz. Always jazz and peanuts. Alice Coltrane especially and Miles Davis’s In a Silent Way is always playing at night wherever I am.

Is there anything in your studio that a visitor might find surprising?

I use power sanders with abrasive sanding pads to unearth layers of paint and uncover forms and colors hidden beneath the surface. My paintings contain an enigmatic quality to them because of this process of sanding down and re-painting. You have to have a lot of patience because the paint has to dry otherwise everything becomes a big swampy mess.

Painting is monastic for me; it requires a life of total devotion. I more or less don’t do anything else.

“Megan Rooney: Echoes and Hours” is on view at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge through October 6, 2024.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

References: this article is based on content originally published by Jo Lawson-Tancred on Artnet. You can read the full article here.